Federal Policy Meets Rural Systems: Why HUD’s New Criminal Screening Guidance Creates Unique Rural Risks

Executive Summary

HUD’s recent decision to rescind its 2015 arrest-record guidance was framed as a national recommitment to “safety” in federally assisted housing. But national policy is never just national. It hits different places in profoundly different ways.

In the Northern Shenandoah Valley — a region without a Public Housing Authority, without local compliance staff, and without a coordinated infrastructure to interpret HUD memos — this shift will not land as intended.

Instead, it will amplify structural weaknesses already embedded in our fragmented housing system:

PBRA senior buildings governed by HUD directives

LIHTC developments that imitate HUD rules but are not bound by them

USDA 515 rural rental properties operating with limited guidance

Voucher landlords navigating complex rules alone

No centralized entity to translate federal guidance into equitable practice

The consequences are predictable: policy confusion, over-correction, increased denials, destabilized seniors, reduced voucher participation, fractured landlord relationships, and elevated Fair Housing risk.

This report identifies significant structural vulnerabilities within rural housing systems and offers a reasoned account of how HUD’s policy shift could unfold across these environments. Its analysis is grounded in the realities of fragmented landlord capacity, limited oversight, and the layered nature of rural subsidy programs. However, the report does not yet provide quantitative evidence demonstrating increases in denials, evictions, homelessness, or voucher non-participation following the memo’s release. The argument is therefore plausible and urgent — but not yet conclusive.

To determine whether these projected risks materialize, rural communities will need sustained monitoring, accessible data, and mechanisms to track outcomes over time. Rather than serving as definitive proof that harm has already occurred, this report functions as a timely call to attention — an invitation for rural stakeholders to prepare, to observe closely, and to advocate for safeguards that align federal policy with local capacity.

HUD intended to promote safety. But in regions like the Northern Shenandoah Valley, the memo may unintentionally undermine housing stability for the very households the agency aims to protect.

Groundwork Strategies developed this analysis to help local partners understand the stakes, strengthen their systems, and prevent avoidable harm.

A Note on Context

On September 26, 2025, HUD rescinded the 2015 guidance that limited the use of arrest records in housing decisions. Two months later, on November 25, HUD Secretary Scott Turner released a public letter declaring a renewed focus on safety in federally assisted housing. Most national headlines haven’t even tackled this because they are focusing on HUD’s crackdown on criminal activity in homeless shelters and Continuums of Care.

That frame dominating the press cycle makes sense. Continuums of Care are the visible front line — the emergency shelters, outreach teams, and homelessness services that readers immediately recognize. [Note: we will discuss this in more detail at a later date.]

But that media framing misses the far larger truth: HUD’s largely ignored memo applies to every HUD-assisted housing program in the country.

And in regions like the Northern Shenandoah Valley, where there is no PHA to filter or contextualize federal guidance, the ripple effects extend far beyond homelessness systems. This memo was written assuming: PHAs exist; they will interpret the memo; they will screen, enforce and train.

But in the NSV:

there is no PHA

voucher landlords are the ones screening

rural owners rely on headlines, not nuance

USDA 515 and LIHTC are not directly governed but behave reactively

capacity gaps magnify misinterpretation

Thus a national memo written for a national system does not account for the structure or vulnerabilities of rural housing ecosystems. The letter encouraged owners to increase criminal screening, monitor residents more closely, and use termination authority when threats to safety are perceived. So what HUD intends as “clarification” becomes, in practice:

illegal screening based on arrest records

blanket criminal bans

excessive termination in senior housing

dramatic reductions in voucher lease-up

increased homelessness caused by rental instability

HUD’s goal was to strengthen safety. Its method was to restore a One Strike style posture. But the effect in rural regions like the Northern Shenandoah Valley will be very different from what the memo intended.

1. The Northern Shenandoah Valley Has No Public Housing Authority

This single fact shapes everything.

The City of Winchester’s HUD required Annual Action Plan confirms that the entire region has no local PHA. Instead, all voucher administration is handled by Virginia Housing, the statewide agency. This includes:

Winchester

Frederick County

Clarke County

Shenandoah County

Page County

Warren County

Without a PHA, the region does not have:

local compliance staff

formal screening review

structured grievance processes

staff who interpret HUD memos

resident services or tenant outreach

internal Fair Housing experts

In other regions, PHAs act as shock absorbers for federal policy shifts. In the NSV, there is no shock absorber. The memo lands directly on property owners and landlords.

2. How Vouchers Actually Work Here — and Why That Matters

Virginia Housing screens voucher applicants only for program eligibility, which includes income limits and two federally required exclusions: lifetime sex offender registration and methamphetamine production in federally assisted housing.

Landlords screen for tenancy. They control:

criminal background checks

credit checks

rental history requirements

household composition decisions

acceptance or denial

When HUD issues a memo encouraging stronger screening, the party that responds is not Virginia Housing. It is the rural landlord who reads the headline and believes that HUD wants more aggressive screening.

This misunderstanding creates real risk. Landlords may begin using arrest records or broad criminal exclusions that violate Fair Housing law. Voucher families then experience increased denials, fewer unit options, and higher risk of homelessness.

3. Rural Landlords and Small Property Management Firms Are the Most Exposed

In the NSV, the majority of voucher rental stock is controlled by:

landlords with one to four units

retirees renting inherited properties

family run rental portfolios

small management firms with limited staffing

These landlords do not receive federal training. They do not have compliance staff. They rarely know the difference between HUD eligibility rules and Fair Housing requirements.

When they see HUD’s memo, they interpret it as a directive to crack down. This leads to:

increased denials of applicants

incorrect use of arrest records

more nonrenewals

inconsistent enforcement across properties

reduced voucher participation

legal exposure they do not recognize

HUD’s memo did not change the law, but it changed the tone. In rural settings, tone often governs behavior more than statute.

4. Beyond Vouchers: The NSV’s Assisted Housing System Is Layered and Fragile

When people think about federal housing assistance, they often think only of vouchers. But in the Northern Shenandoah Valley, vouchers are just one strand in a complex web of programs, properties, and regulatory bodies that hold the region’s affordable housing system together.

This system is not centralized.

It is not uniform.

It is not coordinated.

It is a patchwork — stitched over decades by HUD, USDA, Virginia Housing, and private owners, each operating under different rules, timelines, and oversight structures. In urban centers, these layers rest on institutional scaffolding: PHAs, compliance departments, Fair Housing offices, staff attorneys.

But in the NSV, those layers rest on people: senior housing managers, rural property owners, overstretched LIHTC staff, and landlords who do their best but rarely receive training.

That is why HUD’s November 2025 memo — even though it was framed narrowly around criminal screening — ripples through this system far beyond the voucher program. The region’s affordable housing depends on three overlapping federal programs.

Let’s explain the core programs

PBRA and Section 202/PRAC Senior Housing

Direct HUD Oversight Meets Highly Vulnerable Residents

Senior HUD properties—like Winchester House and Senseney Place—are the most tightly tethered to HUD’s regulatory language. When HUD speaks, these properties do not interpret; they comply.

Under the new “safety” framing, managers feel pressure to:

scrutinize behavior

tighten monitoring

accelerate termination processes

treat ambiguous situations as potential threats

But these buildings house:

adults with dementia

residents experiencing cognitive decline

people with mobility challenges

seniors with mental health needs

individuals whose disability-related behavior may look like “risk”

The risk here is not theoretical. A poorly interpreted HUD memo can become:

a termination notice for a confused senior,

a denial for someone who needs a caregiver,

a fear-driven policy change that leaves fragile households adrift.

PBRA properties respond first to HUD’s memo and in senior housing, the margin for misunderstanding is extremely small.

LIHTC Properties With HUD Layers or High Voucher Usage

IRS Rules, HUD Influence, and Rural Capacity Gaps Collide

LIHTC developments are technically governed by the IRS, not HUD.

But in rural markets:

LIHTC managers often lack dedicated compliance officers

the program’s complexity leads owners to mimic HUD standards for “safety”

many LIHTC properties were financed using HUD tools (HOME, Section 8 conversions, 236 mortgages)

voucher tenants make up large portions of LIHTC occupancy

So even though the memo is not binding on LIHTC properties, the influence is real.

When HUD says, “screen more aggressively,” here’s what typically happens in rural LIHTC:

owners adopt stricter screening “just to be safe”

staff are uncertain, so they default to caution

voucher tenants are deprioritized

old or minor offenses become grounds for denial

increased documentation burdens fall on residents

LIHTC owners are risk-averse. Without clear guidance, they tilt toward exclusion which shrinks the affordable housing supply for everyone else.

USDA Section 515 Rural Rental Housing

HUD Policy Spillover Hits Properties HUD Does Not Even Govern

USDA’s Section 515 portfolio is one of the last sources of deeply affordable rural housing in America. In the Northern Shenandoah Valley, these properties house:

extremely low-income rural families

workers in agriculture, service, and manufacturing

seniors aging in place

multigenerational households

individuals with no practical alternative housing

But USDA provides:

very limited screening guidance

minimal Fair Housing training

little oversight of local screening practices

So rural managers look to HUD for models — even when they do not have to. This is where the real danger lies:

HUD’s memo now becomes the default playbook for USDA-assisted housing, even though USDA never required such changes.

This produces:

over-correction

illegal use of arrest records

inconsistent enforcement

unnecessary terminations

rising homelessness in counties with no shelters

And because 515 properties are often the only assisted rental option in rural towns, misinterpretation of HUD’s memo does not destabilize a building — it destabilizes an entire county.

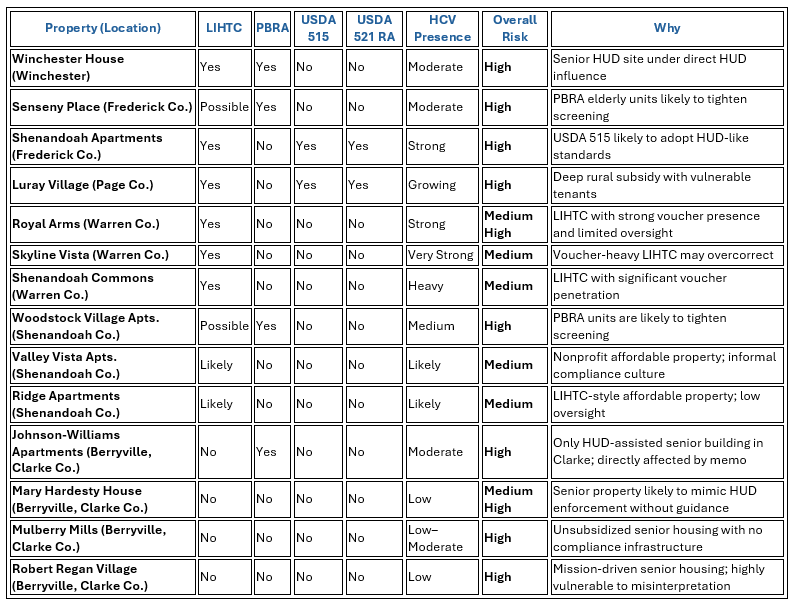

Assisted Housing Risk Matrix for the Northern Shenandoah Valley

Note: This is not an exhaustive list. Property data was compiled from publicly available HUD, USDA, LIHTC, and Virginia Housing sources, combined with verified local knowledge of affordable and senior housing in the Northern Shenandoah Valley.

Why This Layered System Is So Fragile

Each of these programs — PBRA, LIHTC, USDA 515 — was designed with the assumption that housing providers had:

oversight

training

policy interpretation support

legal counsel

staffing capacity

access to continual updates and compliance resources

But in the NSV, most of those supports simply do not exist. So instead of resilience, layering creates:

⚠ fragmentation

⚠ inconsistent interpretation

⚠ varying levels of risk tolerance

⚠ uneven screening practices

⚠ unequal protection for residents

⚠ widespread uncertainty among owners

HUD’s memo is not dangerous because it changes the law. It is dangerous because it changes the narrative environment in a system with little interpretive capacity.

In the NSV, the memo lands not on a stable platform — but on a patchwork of programs already stretched thin. Layered subsidy creates structural fragility. Each program responds differently.

PBRA responds directly to HUD. LIHTC responds indirectly out of caution. USDA 515 responds informally due to lack of guidance. Voucher landlords respond based on perception rather than regulation.

Without a PHA to coordinate screening practices, clarify legal requirements, and enforce Fair Housing standards, the entire system is vulnerable to misinterpretation.

A federal policy shift that was meant to promote safety can unintentionally produce:

higher denial rates

increased evictions

displacement of seniors

reduced voucher lease up

greater homelessness risk

inconsistent enforcement across property types

The memo was national. The impact will be deeply local.

Conclusion: Our Layered System Without a Regional PHA Makes the System More Vulnerable, Not More Resilient

PBRA serves the region’s most vulnerable seniors. LIHTC provides the bulk of modern affordable units. USDA Section 515 housing shelters rural families with few alternatives.

Taken individually, each program is manageable. Taken together, without a local PHA to unify policy interpretation and coordinate screening standards, they form a housing ecosystem that is structurally fragile.

HUD’s enforcement posture now interacts with these vulnerabilities. It can reduce access, increase denials, destabilize residents, and heighten Fair Housing risk in communities already operating at the margins.

Layered subsidy in the NSV is not redundancy. It is exposure. And HUD’s memo did not account for that.

Policy shifts are national. Impacts are local.

Rural communities need clarity, not noise. They need support, not a punitive tone. They need partners who understand how federal policy interacts with rural systems.

Groundwork Strategies exists to help communities navigate exactly these moments, when federal policy moves faster than local capacity and the stability of seniors, families, and extremely low-income residents hang in the balance.

Footnotes

Governance structure sourced from the Northern Shenandoah Valley HOME Consortium 2025–2026 Annual Action Plan (AP 60 Public Housing).

PBRA identification via HUD Multifamily Assistance Property Search, PRAC contract data, and AffordableHousingOnline PBRA flags.

LIHTC layering verified through Virginia Housing allocation records, HUD LIHTC crosswalk, and property-level financing documents.

USDA Section 515 and Section 521 RA properties identified using USDA Rural Development multifamily databases and LIHTC crossover listings.

Voucher program structure and rural landlord behavior informed by Virginia Housing documentation and national research on rural landlord participation.

Glossary of Terms/Acronyms Used in This Article

HUD — U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

Federal agency overseeing public housing, vouchers, project-based housing assistance, and fair housing enforcement. Issued the 2025 criminal-screening memo.

PHA — Public Housing Authority

Local agency that administers vouchers and public housing.

The Northern Shenandoah Valley has no PHA, which shapes how HUD policy is interpreted.

HCV — Housing Choice Voucher Program

Voucher program administered by Virginia Housing in the NSV. Tenants rent in the private market; landlords conduct tenancy screening.

Virginia Housing

The statewide agency administering all vouchers in the NSV. Screens only for program eligibility, not for criminal history.

PBRA — Project-Based Rental Assistance

HUD subsidy tied to units within a property (e.g., Winchester House, Senseny Place). These properties feel HUD’s memo most directly.

PRAC — Project Rental Assistance Contract

Rental assistance attached to HUD Section 202 elderly housing. These senior buildings are highly sensitive to screening/termination shifts.

Section 202 (HUD Elderly Housing)

Affordable housing for very low-income seniors. Often paired with PRAC.

LIHTC — Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

IRS/Virginia Housing program that finances affordable rental housing.

Many rural LIHTC managers imitate HUD screening practices even though HUD does not regulate LIHTC.

USDA 515 — Rural Rental Housing Program

USDA-funded affordable multifamily housing in rural communities.

Managers often follow HUD norms even though they are not governed by HUD.

USDA 521 RA — Rural Rental Assistance

Deep subsidy layered onto Section 515 properties to make rents affordable for extremely low-income rural tenants.

Fair Housing Act (FHA)

Federal civil rights law prohibiting discrimination in housing.

Still limits how criminal records may be used in screening.

Disparate Impact (FHA §100.500)

Fair Housing liability standard that prohibits policies with discriminatory effects — even without discriminatory intent.

Still fully in force after HUD rescinded the arrest-record guidance.

Screening Criteria

The rules landlords use to make admission decisions (credit, rental history, criminal background). Rural landlords often interpret HUD memos incorrectly.

Termination of Assistance / Termination of Tenancy

Ending rental assistance or evicting a household based on alleged criminal activity. HUD’s memo encourages stricter use of this authority in PBRA properties.

One Strike Policy

HUD enforcement philosophy emphasizing removal of tenants involved in criminal activity. The memo signals a return to this posture.

Layered Subsidy

Properties with more than one federal or state program involved (e.g., LIHTC + USDA 515 + RA). Layering increases vulnerability when guidance shifts because no single set of rules governs the property.

Voucher Landlords

Private owners who accept Housing Choice Vouchers. In rural areas, these landlords act without compliance staff and often base decisions on headlines.

Assisted Housing

Housing supported by HUD, USDA, LIHTC, or vouchers. Includes PBRA senior buildings, LIHTC properties, USDA rural housing, and private buildings with voucher tenants.